You can read more about the book ‘Red Lives’ on this link: Red Lives

Bill Alexander (1910-2000)

Bill Alexander commanded the British Battalion of the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War and was for 30 years until his death a leading member of the veterans’ organisation, the International Brigade Association. In various capacities, from IBA vice-chair to secretary, he was a formidable defender of the honour of his comrades in Spain, doing battle in particular with anyone who used Cold War and anti-communist tropes to denigrate the memory of the 2,500 volunteers from the British Isles who went to Spain – and those 530 of them who gave their lives.

Bill was the author in 1982 of ‘British Volunteers for Liberty’, a book that helped revive interest in the International Brigades as the 50th anniversary of the start of the 1936-39 Spanish Civil War approached. He also chaired the International Brigade Memorial appeal, which raised funds for the unveiling in 1985 of the magnificent memorial to the International Brigades, created by sculptor Ian Walters, on London’s Southbank.

As a follow-up to ‘British Volunteers for Liberty’, he wrote ‘No to Franco: The Struggle Never Stopped, 1939-1975’, telling the story of how International Brigade veterans fulfilled their pledge to the Spanish people that they would continue the fight against Franco on their return to Britain. In 1996 he co-authored, with John Gorman and Colin Williams, ‘Memorials of the Spanish Civil War’.

From 1989-96 Bill was the president of the Marx Memorial library in London, home to an extensive archive of documents and artefacts on the Spanish Civil War and the British response to it.

Bill frequently clashed swords with those who sided with George Orwell’s view of the war in Spain, as expressed in ‘Homage to Catalonia, to criticise the role of communists and the Soviet Union. In ‘George Orwell and Spain’ – a chapter in ‘Inside the Myth’, edited by Christopher Norris – he wrote that Orwell had failed to learn the lessons of Spain, that the priority was to defeat fascism and defend the elected Spanish Popular Front government and not to violently pursue ‘hollow phrase-mongering’ revolutionary goals that threatened the war effort.

Just as dismissive was Bill’s verdict on Ken Loach’s 1995 film ‘Land and Freedom, loosely based on the Orwell memoir. He accused it of presenting a narrow and partisan view of the war that exaggerated the role of the few dozen British volunteers with the quasi-Trotskyist POUM militia at the expense of the International Brigaders.

Born into a large, working-class family in rural Hampshire – his father was a carpenter – Bill Alexander joined the Communist Party in 1932, influenced by his mother’s politics and the sight of hunger marchers. His parents encouraged education and he gained entry to Reading University, where he studied chemistry. He then worked as an industrial chemist, but devoted much of his energies to his political and trade union activities, taking part, for example in the October 1936 Battle of Cable Street, which saw the police prevented from clearing a way for Sir Oswald Mosley’s fascist Blackshirts to march through the East End of London.

He joined the International Brigades in the spring of 1937 and was assigned to the 15th Brigade’s Anti-Tank Battery, an elite unit equipped with high-calibre Soviet guns. He became the battery’s political commissar, and was described by a comrade as ‘a strict disciplinarian, but fearless’. Cited for bravery at the Battle at Belchite in September 1937, he was promoted to commander of the British Battalion at the Battle of Teruel, during which he was wounded in the chest and shoulder and eventually repatriated in June 1938.

On his return to Britain he became Merseyside area secretary of the Communist Party until 1940, when he was accepted for a commissioning course at Sandhurst. He finished top of his year and served in North Africa, Italy and Germany, rising to the rank of captain in the Reconnaissance Corps. Resuming full-time party work after the war, he was the Coventry secretary until 1947 (and stood unsuccessfully as a Communist in Coventry East in the 1945 general election). He then spent six years as secretary of the Midlands area, and another six years as secretary for Wales, became assistant general secretary of the party in 1959, a position he held until 1967. He later taught chemistry in south-east London until retirement.

Dorothy Kuya (1932-2013)

By David Horsley.

One of the Communist Party’s most important Black members from the 1940s to the 1980s was Dorothy Kuya. She was born in April 1932 in Liverpool, her mother a Liverpudlian and her father from Sierra Leone. He disappeared and when her mother married a Nigerian, young Dorothy took his surname and regarded him as her father. She and her family lived in Liverpool 8, which was virtually a ghetto, with mainly Black and mixed race families living in one of the oldest Black communities in Britain.

She and her family lived in Liverpool 8, which was virtually a ghetto, with mainly Black and mixed race families living in one of the oldest Black communities in Britain. The inhabitants suffered the worst housing and unemployment. In an interview she remembered “You’d be hard pressed to find a Black face in Liverpool city centre only twenty minutes away by foot”. However, the people of Liverpool 8 were a close-knit community with social clubs that reflected the culture and nationalities in the area.

Young Dorothy Kuya was aware of the class divide and the poverty in the city and the racism and discrimination and as a teenager she joined the Young Communist League. A most confident person even at that early age in the 1940s, she addressed Communist street meetings and regularly sold the Daily Worker. One of her proudest moments was when she met and presented the great African American Paul Robeson, with a bouquet of flowers during his tour of Britain in 1949. Despite the onset of the Cold War with it’s anti Communism she continued to be an active Communist. On a personal level she trained first to be a nurse and then a teacher. In the latter role, she excelled showing her talents as a gifted communicator with the sharpest of minds.

She moved to London, joined her local Party and began teaching in a north London school. Whilst teaching there, she and another Communist teacher, Bridget Harris, set up a pioneering organisation Teachers Against Racism that was particularly active in the 1970s. Her co-worker and friend for many years, Jean Tate, told me that another very influential person in her life was another Communist Ken Forge, who after having lived for a while in Nigeria in the 1930s, was repulsed by the racism there and on return to Britain, joined the Party as a confirmed anti racist. He worked with Dorothy Kuya and became the first person in the country to set up a Black Studies course in a south London comprehensive school.

Alongside her Communist activities, teaching and working with groups on racism, she became involved with a most important journal “Dragons Teeth” which had been started by a radical Indian woman Bandana Ahmed. I well remember as a teacher in those years realising the value of the journal, which investigated, and exposed racism in children’s books and suggested alternatives. In connection with this, she set up a Racism Awareness Unit with funding from Ken Livingstone’s Greater London Council. They had a headquarters in London but when the Thatcher government abolished the G.L.C. that was lost.

As a Communist woman, Dorothy Kuya was a member of the National Assembly of Women and ensured anti racism was on the forefront for the members and she eventually became general secretary of the organisation. They were affiliated to the International Federation of Women and she met many women from the socialist countries as well as progressive women from the capitalist world. Jean Tate told me that a dynamic African American woman Vinie Burrows who visited Britain became a particular friend of Dorothy.

By the 1980s, she was deeply involved in anti racist activities and at the beginning of that decade, spoke at a G.L.C. conference on racism She also participated in a Communist conference on racism and the police in 1981. Her contribution and those of others were published as a Communist Party pamphlet later that year titled “Black and Blue Racism and the Police” By now she had become Head of Race Equality for Haringey Council and worked closely with Bernie Grant MP.

As the divisions in the Communist Party increased in that decade, she drifted away from the party and now devoted her time to working with the Black community and fighting racism. She returned to Liverpool where she had bought a house in Liverpool 8. She worked tirelessly opposing racism and urged the setting up of a slavery museum in the city, as much of Liverpool’s wealth had been as a result of the slave trade. She was overjoyed when the Slavery Museum opened.

Her community work was not over and the next struggle was over the attempts of the Tory government to demolish ten streets in Liverpool 8 as “redevelopment” Dorothy Kuya led the resistance refusing attempts to buy her out and insisted on staying put. Despite the people’s resistance, many homes were demolished. On the cultural and community front, she with others in Liverpool 8 started “African Presence” as a centre celebrating the area’s rich cultural past and it’s connection with the long established African and Caribbean communities.

Dorothy Kuya died on 23rd December 2013. Her whole life was devoted to people’s struggles in the fight against racism and discrimination, she was always a leader. For 40 years she was an active member of the Communist Party who contributed much to the understanding of race and class. A pioneer in many ways, she deserves a prominent place in the history of the Communist Party.

Clem Beckett (1906-1937)

Clem Beckett was a champion speedway rider who throughout his all too short life put his political and trade union values ahead of fame or monetary rewards.

On 12 February 1937 he made the supreme sacrifice while manning a machine-gun at the Battle of Jarama. He was killed fighting Franco’s fascists alongside fellow communist Christopher Caudwell – journalist, poet, Marxist philosopher and novelist (using his real name Christopher St John Sprigg) – with whom he had forged a strong bond of friendship despite their contrasting backgrounds.

Born in Oldham in 1906, Clem became a blacksmith on leaving school and his radical politics were forged in the hardship and discrimination he suffered during the 1920s. He was saved from unemployment and poverty by his unique skills as a speedway motorcyclist and rider on the ‘Wall of Death’.

He began his speedway career in 1928 at Audenshaw, when dirt-track racing was in its infancy, and he was soon the leading rider of his day. By the end of the year he held 28 records in the sport. When he won the Golden Helmet at the Owlerton Stadium, no fewer than 15,000 spectators watched him. His presence was in such demand that he would often have to hire a plane to fly to three different events in a single day. His fame spread across Europe. In 1929 alone he raced and gave displays in France, Germany, Denmark, Yugoslavia and Turkey.

But at the height of his fame, angered by the growing exploitation in the sport, particularly the rising death toll among untrained youngsters, he formed a union for speedway riders, the Dirt Track Riders’ Association. He also wrote an article for the Daily Worker headed ‘Bleeding the men who risk their lives on the dirt track’. In doing so he earned the enmity of the promoters of the sport, the Auto-Cycle Union, who promptly blacklisted him.

Undeterred, he became an exhibition rider, inaugurating the Wall of Death in Sheffield, in which he defied gravity by driving a bike horizontally around a circular wall. In 1931 he toured the continent, including Germany, where he witnesses the rise of fascism, and in the following year he visited the Soviet Union as part of a British Workers’ Sports Federation delegation.

But blacklisting had made life difficult for him, and on his return he took a job at the new Ford factory in Dagenham, where he hoped his interest in mechanics could be put to use. He only lasted two weeks as he was one of the first to try to organise a union in the plant and to publicise the unsafe working conditions in the factory.

During this period Clem was also active in the campaign to gain access to open spaces in what is now the Peak District National Park and took part in the famous 1932 the Kinder Trespass.

His passion for mechanics and engineering led him to set up a motorcycle sales and repair shop on his own account in Oldham Road in Manchester.

But, despite all the success, celebrity and wealth his dare-devil exploits won for him, Clem remained loyal and committed to his working-class origins and socialist philosophy. So, when in 1936 General Franco launched his fascist uprising against the Spanish Republic and Britain refused to sell arms to the Popular Front government, he offered to become part of the International Brigades.

In November of that year he set off to join the anti-fascist forces, in which he was in turn a mechanic, ambulance driver and machine-gunner. He explained why he had gone in the most simple terms and honest way in a letter to his wife: ‘I’m sure you’ll realise that I should never have been satisfied had I not assisted.’

Beckett died in the fighting in the River Jarama valley south-east of Madrid, where Franco tried unsuccessfully to cut the main road to Valencia, which was the capital’s life-line. He was one of 150 members of the British Battalion to be killed.

His friend George Sinfield said: ‘As his section was ordered to retire, Clem kept his machine-gun trained on the advancing fascists, acting as cover to the retreat. The advance was halted but Clem lost his life.’

Clem’s widow Leda captured the spirit of the man: ‘He went to Spain to face death because he loved life.’ He had lived just 31 years.

Alec ‘Spike’ Robson (1895-1979)

By Martin Levy.

Alec Robson was born on 18 March 1895 into a coalmining family in South Shields. At age 11 he started work at the Cambois pit near Blyth, participating in 1910 in the national miners’ strike for an 8-hour day. At age 16 he joined a boxing booth, travelling country fairs and boxing for a living. He probably got called ‘Spike’ because of a South Shields professional boxer of the same name.

In 1912 Spike joined a tramp ship as a cabin boy, sailing first to Novorossiysk on the Black Sea, where he saw political prisoners chained together. On the next leg, he learned from an old sailor about the Battleship Potemkin, the Tolpuddle Martyrs, theChartists and the Mutiny on the Nore. Arriving in New York, he boxed around the UnitedStates, but on the outbreak of World War 1 returned to Britain and joined the Army. He was wounded twice, and awarded the Distinguished Conduct and Military Medals. Demobbed in 1919, Spike married his sweetheart Evelyn and then signed as a stoker on the SS Tzarita, carrying 700 British troops for Murmansk and Archalgensk.

Fraternising with Red Guards in Murmansk, he learned about the class struggle, and on return to Liverpool joined the ‘Hands Off Russia’ movement. During the winter of 1920-1, unemployed in London, he came across a protest march which led to his joining the Communist Party and becoming active in the seamen’s section of the Minority Movement (MM), and in the National Unemployed Workers’ Movement (NUWM).

In 1926, the National Union of Seamen (NUS) was expelled from the TUC for opposing the General Strike. The union was largely a management stooge at the time, and the MM sought to form a new Union of Seamen and get it affiliated to the International Seamen and Harbour Workers (ISH). That failed, but in 1932 Spike was elected onto the ISH executive committee, and in 1933 he was active in the campaign to free imprisoned German Communist leader Ernst Thälmann.

Spike was a fighter, not only for the rights and freedoms of British workers and their families, but against the oppression of working people of all races, creeds and lands. In July 1931, he defended, against an angry crowd of 500+ white sailors, the right of local Arab seamen, who were union members, to join the crew of a South Shields ship. The next month he led an MM occupation of the local NUS office to demand the transfer of an official who had been blocking members in arrears from getting work. In 1932 he addressed mass meetings and demonstrations against the Means Test and the Public Assistance Committee; after the police charged one demonstration he was arrested and gaoled for 4 months.

In 1933, during the Japanese war on China, Spike was arrested again and fined, this time over the SS Stanleyville, which was at Blyth harbour to take scrap iron to Japan.

He spoke at migrant seamen’s boarding lodges, getting the ship blacked so that it only sailed after a long delay. He was arrested and gaoled in North Shields in July 1934 when he “appeared to collide” with a fascist speaker; and then the following year he was arrested in Cape Town, and deported, for organising a petition and protests against the SS Julius Caesar, which was loading material for the Italian invasion of Abyssinia.

In early 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, Spike was shipped on the SS Linaria in Boston, USA, when the crew learned that they were to deliver nitrates to Seville, the fascists’ headquarters. Suspecting that the cargo was to be used for explosives, Spike led the crew in holding a sit-down strike for 3 weeks. They were deported and charged at Liverpool under the Merchant Shipping Acts. They were fined for “impeding the navigation of a ship”, but this was overturned on appeal.

Blacklisted until the outbreak of World War 2, Spike then joined the Royal Navy as a petty officer. His activities included landing in Yugoslavia with supplies for the partisans, and teaching them to throw and detonate hand grenades.

After the war, Spike went back into the Merchant Navy, and in 1947 became the first communist to be elected onto the NUS executive. Under the impact of Spike and other left-wingers, the union had changed, and the living conditions on board ships were transformed from the squalor that seamen had to endure before the war. He continued his union activities till retirement, and died in November 1979.

Sources: Spike … Alec ‘Spike’ Robson 1895-1979, Class Fighter, North Tyneside Trades Union Council, 1987; Don Watson, No Justice Without a Struggle: The National Unemployed Workers’ Movement in the North East of England, 1920-1940, Merlin Press, 2014.

Charlie Hutchison (1918-1993)

Charlie Hutchison was unique in more ways than one. A Black Communist who spent ten years physically fighting fascism and racism from Cable Street, Franco’s fascists in Spain to Hitler’s nazis in France, North Africa, Italy and Germany. Born in Oxfordshire on 10th May 1918, his father was from the Gold Coast (Ghana) and his mother a local woman. The couple had five children and Charlie’s father often traveled back to Africa and eventually did not return, leaving his wife in financial hardship as well as mental anguish . Concerned for her children, she asked for Charlie and one of his sisters to be taken temporarily into care and so they went to the National Children’s Home and Orphanage in Harpenden He and his sister spent several years there until he was allowed to leave and joined his mother who now lived in Fulham.

By 1935, working as a lorry driver and aware of his race and class, he joined the local Y.C.L. and was quickly elected chair of the branch. Alongside many other Communists, he went to Cable Street when Mosley’s blackshirted fascists attempted their provocative march through the Jewish East End of London and played his part in forcing them to turn away in defeat.

Two months after this in December 1936 , the 18 year old Charlie Hutchison was among the early British volunteers to go to Spain to help defend the Spanish republic from Franco’s fascists supported by Mussolini’s and Hitler’s huge military aid. He gave his reason for going in these words ” I am half Black, I grew up in the National Children’s Home and Orphanage. Fascism meant hunger and war” He has the distinction of being the only Black British volunteer in the International Brigades in that momentous struggle for freedom and against the twin evils of fascism and racism.

Despite his young age, he served for two years until the end of the war in 1938. He fought at the Battle of Lopera soon after his arrival and was wounded during the fighting where the great British Communist and poet John Cornford lost his life. After recovering from his wounds, he refused to be repatriated and because of his youth, was reassigned as an ambulance driver in the Republican Army. His superior officers described him as ” a hard and capable worker” and said his political views were ” Good for his age, quite developed”.

As time passed, and his mother wrote pleading for him to come home, he did ask to go back on temporary leave of absence to deal with family affairs but due to bureaucracy this did not happen so he bravely continued to serve until December 1938. In the 1980s, Charlie Hutchison gave his reason why so many men and women came to Spain to aid the Republic in the International Brigade. He said ” The Brigades came out of the working class, they came out of the Battle of Cable Street, they came out of the struggles on the side turnings…. they weren’t Communist they weren’t Socialist but they were anti-fascist”

Charlie Hutchison hardly had time to resume his duties with the Communist Party in Fulham when the Second World War broke out . He joined the British army, went to France and was among those at Dunkirk in 1940 who were rescued by hundreds of small vessels and the Navy from the advancing nazi forces. He then served in North Africa and through the long bloody campaign in Italy. In the last years of the war, he fought in France and into Germany. In April 1945, he was among British troops who liberated Bergen Belsen Concentration Camp. What he witnessed there, was the ultimate of racist fascist ideology, the extreme barbarism he had been fighting for ten years.

He resumed life in Fulham and in 1947, married Patricia Holloway, a fellow Communist . A life long Communist, Charlie Hutchison died in 1993 and was rightly honoured at at an event in 2019 attended by many proud family members . His son John, speaking of his father, remembered growing up in a house full of books “by Marx, Salinger, Steinbeck and Hugo” He also said, ” unusually for the ’50s and ’60s he had friends from all over the world through the Communist movement” Charlie Hutchison, this unique Black Communist, anti racist and anti fascist is well summed up by his son John’s words ” My father believed in the family of man”

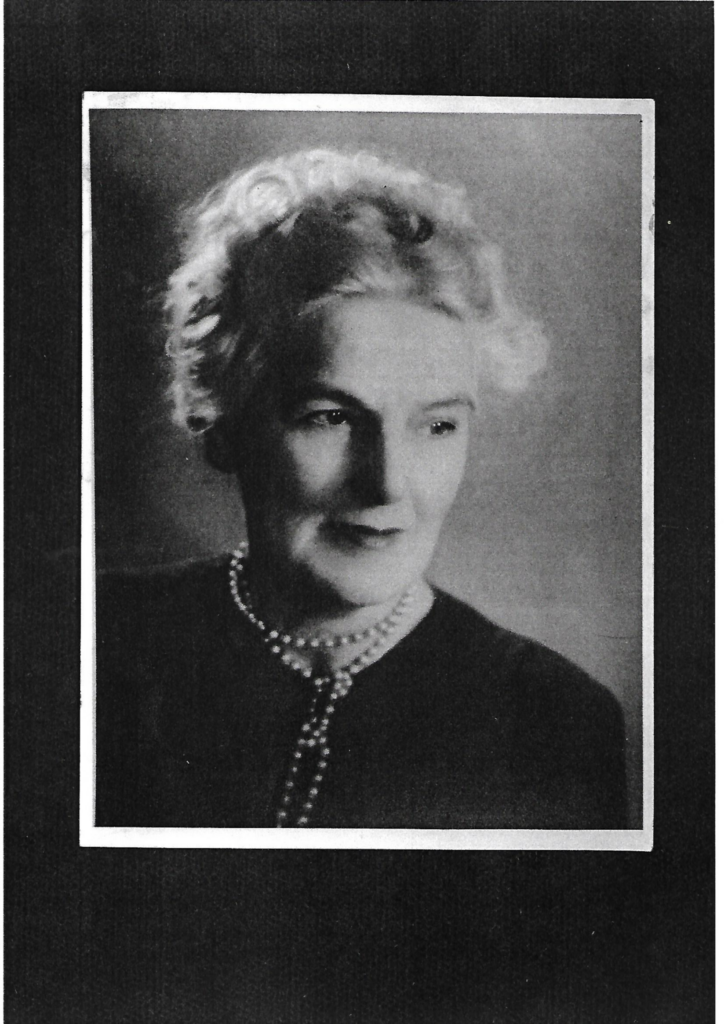

Fanny Deakin (1883-1968)

By Birmingham & District Plus CP branch.

Black Country man, Unison activist turned PhD student and Midlands Communist Party Chair, Andrew Maybury, on reading the bare bones of Councillor Fanny Deakin’s life felt that “it’s not possible to stop yourself from being amazed by it. Single-handedly, for a Communist to win over a whole community to the extent that decades after her death people are still wowed by her. She was clearly both single-minded and so full of integrity that people believed in her. What a lesson for today’s politicians!”.

Born on 2nd December 1883, Fanny Rebecca Davenport spent her early years at her parent’s farm on Farmers Bank, Silverdale, a mining village near Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire, which is today near to Keele Golf Course. She married Noah Deakin in 1901, when her address was “Racecourse Back Lane, Silverdale” and she and her husband moved to Wolstanton, today on the north side of Stoke-on-Trent.

Throughout her life, she was noted for her campaigns for better nourishment of young children and maternity care for mothers. On leaving school, she worked on the farm where her family lived but her lifelong vocation came to her after being the first woman to be elected onto Wolstanton Council as a Labour member in 1923.

During the General Strike in 1926, she was a major figure in local activity in support of the miners. One observer recalled seeing her “coming up past St Giles Church in Newcastle-under-Lyme at the head of these miners, 200 or 300 miners …Fancy, one woman – and she’s leading them!” She herself used to say: ‘I’m fighting for the mothers. If she had a coat of/arms they’d put it in Latin: Fighting for the mothers.” In 1927 she retained her seat, this time standing as a Communist. She was very popular with local people, who nicknamed her “Red Fanny” after she visited the Soviet Union in 1927 and 1930.

Of her five children only one survived into adulthood. In an era of high infant mortality she campaigned for better maternity care of women and free milk for children under five. Along with unemployed miners, she went to Downing Street to see Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald to demand that local councils give free milk to pregnant mothers and children up to the age of five.

Her selflessness was displayed when a comrade was found guilty of supposedly inciting a riot of the unemployed, Fanny gave him an alibi but found herself charged with perjury and spent nine months in Winson Green Prison. It only seemed to help her electoral chances!

Re-elected to the now merged Newcastle Council in 1934, again as a Communist, she became a County Councillor. She played a key role in several committees relating to maternity and child welfare. During the war years she could be seen working with others in the Catholic Church showing children how to put on gas masks. In 1941, she became the first Communist in the country to be appointed an Alderman, in this case for the Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough, with the honour being extended to Staffordshire county level in 1946.

The following year, she achieved what most local people remember her for when a maternity home was opened bearing her name for use by the women of the Borough. Her advocacy of mother and child welfare issues was marked by the naming of the Fanny Deakin Maternity Home by the Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council. She is still popularly remembered through the many children born there and also due to a GP ward named after her in a local hospital.

Although Fanny died on 24th March 1968, she is still regularly remembered locally. In 1991 Joyce Holliday wrote “Go See Fanny Deakin!”, in which Fanny Deakin appears as heroine in a play centred on the mining community of Silverdale. It was subsequently broadcast by BBC local radio. Joyce Holliday also wrote “Silverdale People” which includes a biography of Fanny Deakin.

Sources include: Comment 25 May 1968, Fanny Deakin’s papers in Newcastle Library, including manuscript autobiographical notebook written in 1966-7, https://grahamstevenson.me.uk/2008/09/19/fanny-deakin/

Ivy Woods (1914 -2005)

By Eleanor Lewington

Ivy Oliver was born in Holborn, London in 1914, living above the shop where her father was a grocer. In the mid 1920’s, after stopping a bailiff removing Freemason’s regalia from a tenant’s flat, he lost his trade from all the surrounding hotels when he refused to join them.

They moved to Bristol in 1926, where she lived for the rest of her life.

She worked in the Bristol Central Library, where she met her future husband, Stephen Woods (who was already in the Party), married in August 1939, and had three children. She joined the Party in 1940 (when many people were leaving!) At a time when members were encouraged to spend at least half their time on work outside the party, she joined the Sea Mills Coop Guild, and soon became secretary.

The President of the Bristol Cooperative Society was a Communist Jack Webb, and he got Ivy involved in structures in the Coop. By 1946 she was attending Society meetings. She was elected to the Society Party (Political Committee) in 1947, and immediately faced hostility as a member of the CP. This was the time of bans and proscriptions. She got defeated in 1951; she was on the Political Committee for a total of 8 years, standing 24 times! She was elected to the Management Committee in 1964 at the 14th attempt. Other than a break of a year after a defeat in 1975 for one year, she had continuous service.

She did not slacken that year, as she took on adult literacy work. It was the time of “On the Move”, and she got huge satisfaction helping Caribbean women to learn to read.

At the same time as all this Coop activity, she took on positions in the Party. She was a strong supporter of the Daily Worker /Morning Star. In the war she sold regularly at the dock gates, and was still selling at a pitch in Shirehampton, Bristol in 1988 on a Saturday morning. She was a regular bazaar supporter: her speciality was coconut ice, vanilla, pink and chocolate.

She was a member of the West of England District of the Communist Party for 30 years, 12 years in the Chair, and 9 years as district treasurer.

She went on the Communist Party’s Women’s delegation to the Soviet Union in 1963, led by Gladys Easton, the first to visit Siberia (Irkurtz and Novosibirsk) and Leningrad and returned early to Moscow to meet, at a party restaurant, Valentina Tereshkova, who had just returned from space, along with Yuri Gagarin and Valery Bykovsky.

When she returned Ivy gave at least 50 report back meetings. Several of these will have been to Coop Guilds.

She was giving talks to Women’s Guilds by 1950. There are notes on the topics of Economics of Cooperation, which started with the background to the Rochdale Pioneers, and the eight principles. She gave a number of talks on women in the period from 1953-5 Women through the Ages, a history of women. A series of talks in 1956-7 on new prospects for women, dealing with women’s current position.

There were about 28 Women’s Guilds in the 50’s in the Bristol area, and in any on lecture year, which ran from October to May, she was doing about 20 talks or more, to a dozen guilds, with two or three topics on the go each year.

Ivy was also very active in the Peace Movement, and a lot of her talks were on peace: the immorality of war, the vested interests of the arms industry; against the H bomb tests in 1957; discussions on Unilateral Disarmament, and Aldermaston marches.

In 1968 she spoke to a rally in Bristol against the war in Vietnam.

A real love of peace is something active. It is not passive.

It is good, but of little practical value at this time, just to want peace, if you are not prepared to do something about it.

As a woman and a Co-operator of our city of Bristol, I am speaking to the people of Bristol.

We women want peace and we women mean to have it.

Ivy Woods

Sam Watts (1925 – 2014)

By Kevan Nelson.

‘They don’t realise that strength they’ve got, do they? They don’t realise that power they’ve got – the working class can change the whole history, as quick as that, they just don’t realise, they haven’t grasped it’ said veteran Communist Sam Watts in his stand out contribution to Ken Loach’s 2013 film The Spirit of ’45.

Sam was a formidable and lifelong Communist Party member in his native Merseyside.

Born in February 1925 in Liverpool’s Great Homer Street area, he lived through the direst poverty as a child, which he described eloquently when interviewed for Ken Loach’s 2013 film The Spirit of 45 – “I was the third of eight children, living in the worst slums in Europe, sleeping five in a bed. The house was full of vermin — bed bugs, cockroaches, fleas, rats. There was nothing we could do. We couldn’t get rid of them”

Three siblings died in childhood, two at the same time, prompting Sam’s memory of his family travelling to the cemetery in a one-horse carriage bearing two coffins on their knees before burial in a pauper’s grave. His mother’s task was not eased by the removal in 1933 of her husband, who had worked in a timber yard, to what was then called the lunatic asylum at Rainhill. He suffered from post-traumatic stress brought on by experiences in the first world war trenches that were further aggravated by his brother William’s execution for supposed cowardice.

Sam’s father remained in Rainhill without speaking until he died in 1943. In reality, William was suffering from shell-shock and exposure to gas, as were many of the 306 British soldiers shot by firing squad in that conflict. Sam campaigned for years for these men to be pardoned and was delighted in 2006 when this was belatedly agreed.

He had proudly but provocatively waited in line on Armistice Day to incur the wrath of the British Legion by laying a wreath of white poppies at the war memorial in memory of the uncle he had never known. Sam joined the Royal Navy in 1943, but, after being demobbed, he returned to the same slum conditions before going to London to seek work.

Eventually, he found work at a Lyons Corner House where he cleaned the place in the morning before donning a brown suit, peaked cap and white gloves in the afternoon to welcome customers. “Every night I joined the long queue to get a bed in the Salvation Army hostel, as I had no money for proper rent,” he said.

Returning to Liverpool, he survived on dead-end jobs and then benefited from the post-war economic upturn to find work as a rigger on Liverpool docks and become a shop steward. Although he had never been a great reader, he was given The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists by a workmate on the docks. “It opened my eyes to many things, to life and how we were being conned,” he said. “I was invited by leading Mersey Docks shop steward Alec ‘Bunny’ McKechnie to attend a Communist Party rally at St Georges Hall in Liverpool.

“It was addressed by general secretary Harry Pollitt and I joined the party at that meeting. I became a regular reader and seller of the Daily Worker from then onwards.”

From that day until his death at the end of 2014, Sam spent over 60 years as a Communist Party activist. His activities included being lifted, literally, by police when he protested against Margaret Thatcher’s visit to the Eldonian housing estate in Liverpool’s Docklands in 1989. He was also for decades the party’s Morning Star organiser, collecting a quire every morning before cycling around Liverpool’s trade union offices to sell them their daily paper.

He was in no doubt that the real problem was a clapped-out economic system. “The capitalist system is finished. It just doesn’t work any more. You can’t make it work. The only answer is socialism to get the country back on its feet.”

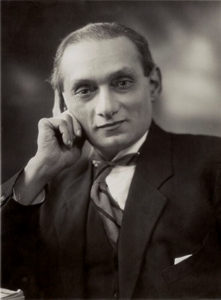

Shapurji Saklatvala (1874-1936)

By Mike Squires.

Shapurji Saklatvala, Sak to those who knew him, was briefly the Labour MP and then the Communist MP for Battersea North in South west London in the 1920s.

He was a remarkable individual. Born into the wealthiest family in India he came to Britain in 1905. Originally for a short stay but upon meeting his future wife, who was English, he made Britain his home.

Already a supporter of the Indian National Congress upon his arrival he gradually became influenced by socialist writers and speakers and joined both the Independent Labour Party and the Social Democratic Federation. After the outbreak of the First World War he became an increasingly active member of the ILP.

His involvement brought him to national prominence. Influenced by the Russian Revolution he moved to the left.

In 1921 he was adopted as the Labour candidate for Battersea. There were no bans on Communist party members being members of the Labour party. Sak had joined the CPGB soon after the ILP’s refusal to affiliate to the Communist International in March 1921.

At the 1922 General Election he was elected as the Labour MP for Battersea North. Defeated at another election the same year he was re-elected at a third election in 1924. This time who was returned as a Communist MP although backed by the left leaning local Labour party and trades council. There were still no bans on CP members being members of the Labour party. This did not come into force until 1925.

He remained Battersea’s MP until defeated by a Labour candidate at the 1929 election. By this time communists could no longer be members of the Labour party.

Unlike many Labour MPs Sak involved himself in the extra parliamentary struggle. Arrested in 1926 during the General Strike on his realise he addressed mass meetings all over the country. He was a fantastic orator and one of the CPs leading and popular speakers.

While an MP, he visited India in 1927 and met with Gandhi. Both men agreed over India’s freedom from British rule but disagreed how this was to be achieved. While there Sak meet many Indian communists and laid the basis for the cotton workers strike in Meerut, which lead to the famous Meerut Conspiracy Trial.

Through his political life Sak was active in India’s liberation movement. Through organisation like the Workers Welfare League of India which raised awareness amongst British workers about India’s plight, through to the Indian National Congress of which he was a London member. He wrote pamphlets about India, contributed to Commissions on India’s welfare and was regarded by some in the right wing media as India’s MP in parliament.

He was knowledgable on India and had it not been for his commitment to the Communist party his secretary during his time in parliament believes that he could have become Labour’s spokesperson for the colonies. High office indeed.

Sak’s life does blow rather a hole in the argument of many commentators of CPGH history. They all argue, with some honourable exceptions that British communists were dictated to by Moscow through the Communist International. This is particularly so with the adoption of the Class against Class policy from 1929-35.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Sak was advocating such a policy from 1925 onwards. His experiences of Labour in power and its lack of support for the Labour movement, and India, led him to write a letter to the party’s Executive Committee three years before Class against Class, urging them to change the party’s policy in exactly the direction advocated by the Class against Class strategists.

After his election defeat in 1929 Sak stood as Communist candidate again in Battersea, but also in Shettleston in Glasgow at a bye election.

He spoke at a whole number of meetings in support of the party’s new daily paper, the Daily Worker, launched in 1930.

In 1934 he visited the Soviet Union and was very impressed with the Union’s eastern republics which were Muslin. He spoke at meetings about the progress they had made under Soviet rule on his return. It was on his visit that he suffered a heart attack.

He survived another two years and died in January 1936.

Harry Pollitt, the party leader led the oration at Sak’s cremation in Golders Green Crematorium.

Apart from his political life Sak was a devoted family man. He met his English wife in Derbyshire soon after his arrival here. They married and had five children. Living most of their life near Parliament Hill Fields in London.

As Harry Pollitt said at his funeral, “He will live again in work to come”